This is all about scale and distance. When I’m standing looking at the ground, there seems to be nothing flowering, just a lot of low leaf growth. But if I bend over and look closely, in the green around my shoes there are a few points of colour. Winter and early spring flowers seem to be mostly small – I suppose the plants are running on their reserves in swollen roots, or on the small amount of solar energy from the winter sun. So in this post I’ve tried to get closer with the macro lens and see how amazing these little flowers are.

Here’s one of the prettiest, just visible in the centre of the first photo – but only showing its full splendour when photographed in macro and enlarged. It’s Veronica persica, Persian or bird’s eye speedwell, distinguished from similar species by its deep colour, prostrate habit and flower stalks longer than the leaves. I took this picture in January.

The way these flowers are studded in the ground cover reminded me of a garden in Wales: the cloister garden at Aberglasney in Carmarthenshire, where small flowers were planted in formal grass beds or parterres, an effect called ‘enamelling’ – you can see Aberglasney here. This garden fashion dates from around 1600, and contrary to today’s tastes, the ideal viewing point was thought to be well above – hence the raised stone walkway round the cloister, which originally caused some scratching of heads among the garden restorers at Aberglasney. This style of planting replaced the earlier formal garden habit of carefully shaped flower beds surrounded by box hedges, also best seen from a terrace or walkway above, and called compartiments de broderie. Embroidery, or enamel brooches: Nature was not only to be tamed, but miniaturised enough to be held in the hand.

Anyway, for 21st-century tastes, on with the magnifications, and here’s another deadnettle I found this week. If you compare it to the plant in the last post, you can see that in this one, the henbit deadnettle (Lamium amplexicaule), the leaves are unstalked, enclosing the stem, and the flowers have a much longer corolla tube.

I also found another stork’s bill (Erodium) – I blogged E malacoides on 8th December here. This one’s E. cicutarium, common stork’s bill, also from January, though there are a couple in the right of the first picture too. You can see the characteristically pinnately-lobed leaves (lobes in rows each side of the stalk), deeply cut in this species, which also has fleshy stems.

True Geranium flowers are often similar to those of stork’s bills, but the leaves are always palmately lobed in that genus, radiating like fingers from a palm.

I’d have to go back when they’re fully open, but mostly here I see the tasselled Muscari comosum, which I blogged on 3rd September here. These could be Muscari neglectum – common grape hyacinth. Then a lovely spurge which I can’t identify till it opens fully.

On the opposite side of the road the yellow heads of Euphorbia segetalis had fully colonised a neglected vineyard (with a few beautiful big sun spurges – E. helioscopa). You know I have a thing about spurges, and this sight made my day.

And finally you may have noticed the yellow composite flowers in the first photo – here are some more on a stony hillside:

I think they’re a species of hawkweed (Hieracium) but since there are at least 800 species I’m not going to try to guess which one. Curiously they can produce seed asexually, and thus produce lots of identical clones in a neighbourhood, and it’s hard to tell what’s a clone or variety and what’s a species. If you count all the different forms described for this genus, there are 10,000!

Back to the title of this post and the lovely blue speedwell, this is ‘Veronica’, written by Elvis Costello with Paul McCartney, and about Elvis Costello’s grandmother. It’s on the album Spike (1989), his first album for Warners. He had songwriting skill to burn in those days – so many strong songs on one album. This version is from 1989, live outside the offices of his new record label, and acoustic, showing Costello’s fine vocals and driving guitar chord playing which still captures the song’s falling bass lines. The Warner Bros staff don’t look like the most responsive audience he’s ever had – no wonder he shouts ‘Back to work!’ at the end.

While preparing this post, I heard that Dave Brubeck had died, at the age of 91. I got to like his music very much, though at first I had to shake off my feeling that it was a guilty pleasure: should a jazzman be as white as me, classically trained, have a tendency to play fugues and rondos, and be big with the crew-cut Yankee college crowd? What got me over all that was his swing, his melody, and the wonderful quartet he led for 17 years. One thing I admire him for is his willingness to tackle issues with music: for example, with his wife Iola he created the perceptive and funny show The Real Ambassadors, performed at the 1962 Monterey Jazz Festival with Louis Armstrong. It was a critique in jazz of the US State Department tours – a brilliant idea which was so novel it never took off. His quartet also had the great advantage of Paul Desmond on alto sax – not only a perfect partner for Brubeck but also the author of one of the funniest pieces I’ve ever read on jazz. It begins:

You can read the whole piece here – it was to have been part of a history of the group titled after a stewardess’s question: How many of you are there in the quartet? Desmond died in 1977.

Dave’s group will play us out at the end, but for now let’s move on to the botany. This five-petalled pink flower is Erodium malacoides (Erodium a feuilles de mauve in French, Mediterranean stork’s bill in English). So, there are your identifying clues: it has leaves a bit like mallow (mauve), and fruits with elongated stigmas like a stork’s bill – though to be fair, so have most of this genus, this family (Geraniaceae) even. The plants have now grown after the autumn rains and are starting to flower, though their main period is the spring.

Now, I’ve lent all my printed flower guides to a friend, so this was identified with the help of some flower websites. They may not be portable if you don’t have an iPhone, but they do show what’s out there, including plants thought too common, too recently arrived or too invasive to be in the printed guides. They also tend to be more up to date. These below are my own favourites, arranged as a top five to make your very own handy ‘cut out and keep’ guide! They’re all on my ‘Resources and links’ page. Click on the name in bold to go to each site. This will be very tedious reading if you don’t want to put names to blooms, so you might want to skip to the end, and a track from a favourite Brubeck album.

The best by quite a long way: the easiest to use, the most search options, and the best quality photos, usually several per plant, so you can see the details you need for identification: leaves, underside of flower etc. Don’t be put off by the word ‘Alpes’ in the title – the photos come from there but also Provence, Roussillon, Catalunya etc.

In Brief: Language of site: French only. Search for flower by: colour, family and genus, multiple criteria, Latin name, French name, flowering date, random, all plants. Number of plants/photos: 3,162 plants/15,000+ photos. Site run and photos taken by: Franck Le Driant, who also runs botanical field courses in Provence/Alps/Corsica.

This well designed site is easy to use, and while it says it concentrates on north-east Catalunya, this will include very many species common around the western Mediterranean. Other big pluses: Google Translate works pretty well here for headings and most content; and it has a huge range of s. One aim is to preserve traditional plant lore (ethnobotany), so there are interesting links and snippets of info.

In Brief: Language of site: Catalan, though Google Translate gives you a very wide range of alternatives. Search for flower by: scientific name, or name in Catalan, Spanish, French, English or Occitan. Number of plants/photos: about 2,680 species, over 18,000 photos. Site run by: ‘the volunteer work of people who love nature’, coordinated by Albert and Peter Mallol Camprubí Barnola Echenique.

An enthusiast’s labour of love with many pages of information about the département of Pyrenées-Orientales, including its flowers. Useful because it covers very similar flora to the Languedoc, and gives some fun facts, including Catalan names.

In Brief: Language of site: French only. Search for flower by: Lists of family names, scientific names (Genus and species), French names. Gives Catalan names in each entry but not in an index – though the search engine included on the site also works for Catalan names. Number of plants: 1,327 plants: one, sometimes two photos per species. Site run by: Jean Tosti, who cheefully admits he’s a keen amateur rather than a botanist.

There are massive resources on this site, especially the uploads of volunteer collaborators – but these are only as good as the contributor! Lots of documents to download and specialised pages for the scientifically-minded. Useful maps of distribution – but only according to users’ reports. All botanical content open-source.

In Brief: Language of site: French or English (icon in top right of home page), but English seems to work just for headings; most text remains in French. Search for flower by: Scientific name, French name. Number of plants/photos: Total plant number not known, over 70,000 photos! Site run by: an association based at the Institut de Botanique in Montpellier.

‘Plants For A Future (PFAF) is a charitable company, originally set up to support the work of Ken and Addy Fern on their experimental site in Cornwall, where they carried out research and provided information on edible and otherwise useful plants suitable for growing outdoors in a temperate climate’. A good source for food or healing uses – where else can you search for a plant using the words ‘curdling’ or ‘antidandruff’?

In Brief: Language of site: English only. Number of plants/photos: 7,000 species worldwide claimed, most with drawing or photo from wiki sources. Search for flower by: Scientific, common English or family name, and also edible or medicinal uses. Site run by: charitable company, professionally designed site.

A resource of photos only – no text – and not restricted to the Mediterranean. I’m including it because it enables search by colour and other criteria.

In Brief: Language of site: French only. Search for flower by: scientific or French name, or family, or colour, or fruit, or foliage. Number of plants/photos: 2,039 species and 4,026 photos – this may include flowers outside France. Site run by: Olivier Gaubert who took most of the (very good) photos.

Enough of all that, on to the music. From the Brubeck Quartet’s Jazz Impressions of Japan (1964) – an album whose mood reflects real affection for a country they toured – this is a tune written, Brubeck says, in Kyoto: ‘ I was awakened by a sudden clap of thunder. Watching the rain drench the streets below, I thought “The city is crying”, and the words became a melody of another musical impression.’

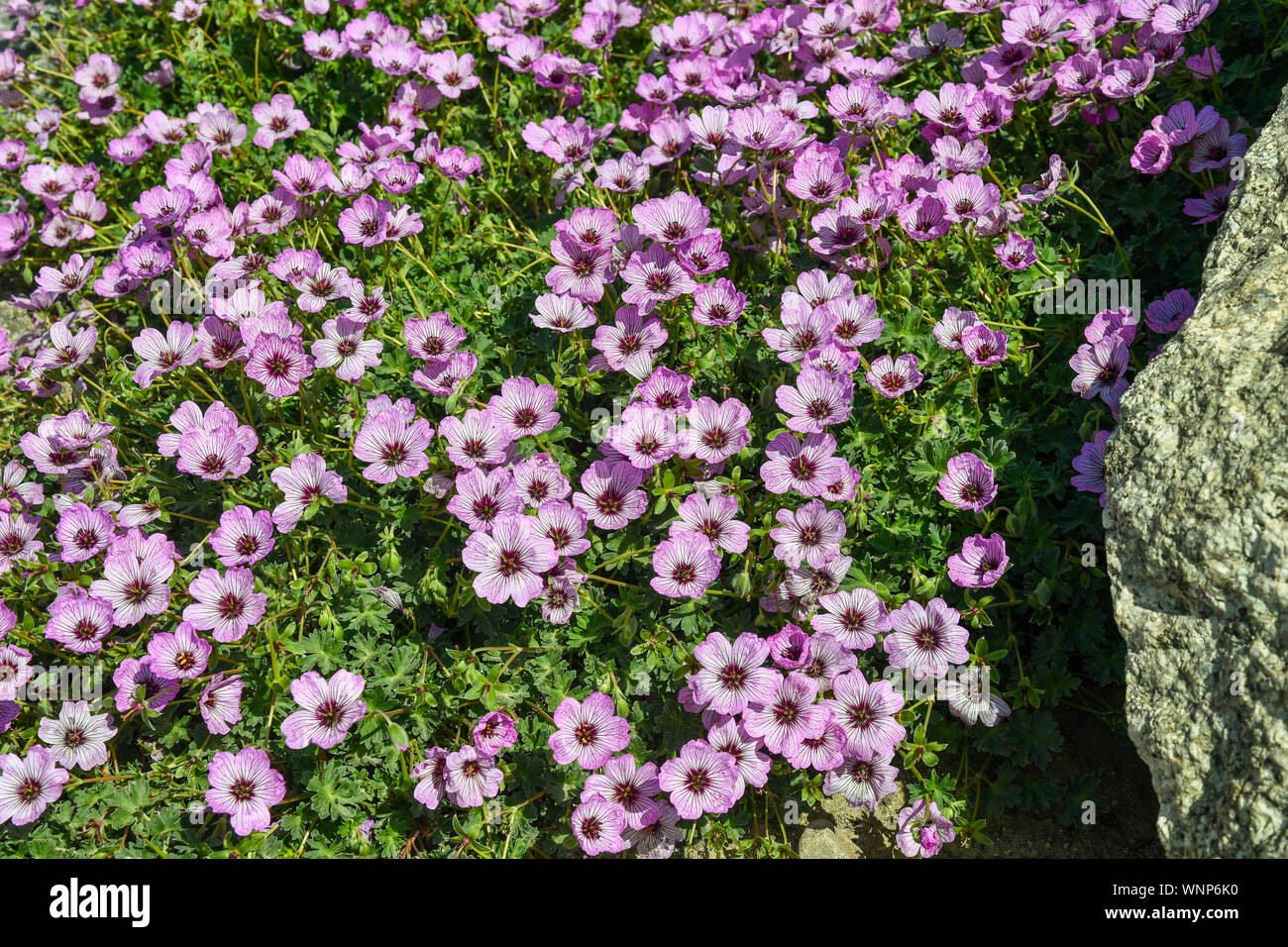

Alpine stork’s bill is a beautiful and delicate flower that can add charm to any garden when planted properly. Determining the right spacing for these flowers is crucial to create a visually pleasing display that allows them to thrive. In this comprehensive guide, we will dive into the ideal spacing requirements and planting tips for your alpine stork’s bill flowers.

With its elegant pink blooms and fern-like foliage, alpine stork’s bill (Erodium reichardii) is a delightful flowering plant suitable for containers and rock gardens. Native to the Mediterranean region, these flowers grow in clumps and prefer well-drained soil and full sun exposure. Their compact size makes them suitable for small spaces.

Alpine stork’s bill belongs to the geranium family but features smaller and more delicate flowers compared to hardy garden geraniums. Grown for their ornamental value and ability to attract pollinators, proper spacing of these flowers can maximize their visual impact

Spacing Guidelines for Optimal Growth

When planting alpine stork’s bill the spacing between each plant will depend on the look you want to achieve. Here are some recommendations

-

Clumped planting (6-8 inches apart): Planting the flowers close together creates a dense carpet that’s ideal for borders and pathways. The clumps will grow into each other seamlessly.

-

Spaced planting (12-18 inches apart): More room between plants allows them to spread out individually. This showcases each flower and promotes bushier growth.

-

Mixed planting: Alternating clumps and individual plants creates an eclectic, free-flowing appearance. Adjust spacing as needed to strike a balance.

Remember to assess factors like your garden’s dimensions and style when deciding on spacing. Adjust spacing over time as the plants grow and fill in.

Planting Tips for Healthy Growth

When planting alpine stork’s bill, follow these tips to help them thrive:

-

Prepare soil with compost or organic matter to improve drainage and nutrition. Stork’s bill prefers slightly alkaline soil.

-

Water new plantings daily until established. Mature plants only need occasional watering.

-

Place them in full sun to part shade. Avoid hot afternoon sun in warmer climates.

-

Apply a balanced liquid fertilizer monthly during spring and summer.

-

Mulch around plants to retain moisture and regulate soil temperature.

-

Prune spent blooms to prolong flowering. Also trim any leggy growth.

-

Repot container plants every 2 years in fresh potting mix to replenish nutrients.

-

Watch for aphids, mites and other common pests. Treat promptly with insecticidal soap.

Achieving Harmony in Your Garden

Play around with alpine stork’s bill placement until you find an arrangement that complements your garden. As a general rule, allow at least 6 inches between plants for adequate airflow and light exposure. Adjust spacing as needed to suit your preferences and garden layout.

For a cohesive look, mass plant clumps of 3-5 plants and repeat throughout the garden bed. Or scatter individual plants in a naturalistic style. For a more structured appearance, plant in rows or grids with consistent spacing between each flower.

Observe how quickly your stork’s bill plants grow and spread to determine if they need dividing or thinning over time. Mature plantings may creep together, creating the need for occasional division to rejuvenate growth.

With its delicate charm and versatility, alpine stork’s bill can beautify gardens, rockeries, mixed borders and container arrangements. Following proper spacing and planting techniques will ensure these delightful blooms put on a stellar floral display.

k

REDSTEM FILAREE California wildflowers, Erodium cicutarium; Common Stork’s Bill,Heron’s Bill,Pinweed

FAQ

How far apart should flowers be planted?

How do you take care of a storksbill plant?

Is Stork’s Bill invasive?

Is storksbill a perennial?

Is stork’s Bill a perennial?

Soils must be well-drained. Drought tolerant once established. Erodium chrysanthum, commonly known as heron’s bill, stork’s bill, or crane’s bill, is a dense, tufted, evergreen perennial in the geranium family.

What does a stork’s Bill look like?

Common Stork’s-bill is hairy plant of dry grasslands, and bare and sandy areas, both inland and around the coast. Its bright pink flowers appear in May and last through the summer until August. The resulting seed pods are shaped like a crane’s bill (hence the name) and explode when ripe, sending the seeds, with their feathery ‘parachutes’, flying.

Where do stork’s bills come from?

Most occur only in isolated locations. The broader Geraniaceae (geranium) family contains numerous species, both native and introduced. The plant’s common name “Stork’s Bill” references the shape of its seedpods, which resemble a stork’s open bill.

Is stork’s Bill a noxious weed?

Colorado calls it a noxious weed. Scientifically Stork’s Bill is called Erodium cicutarium (er-OH-dee-um sik-yoo-TARE-ee-um.) Erodium is from the Greek word Erodios, meaning heron — now there’s a surprise. Cicutarium — Latin — means resembling the genus Cicuta, the Poison Hemlock, and it does.