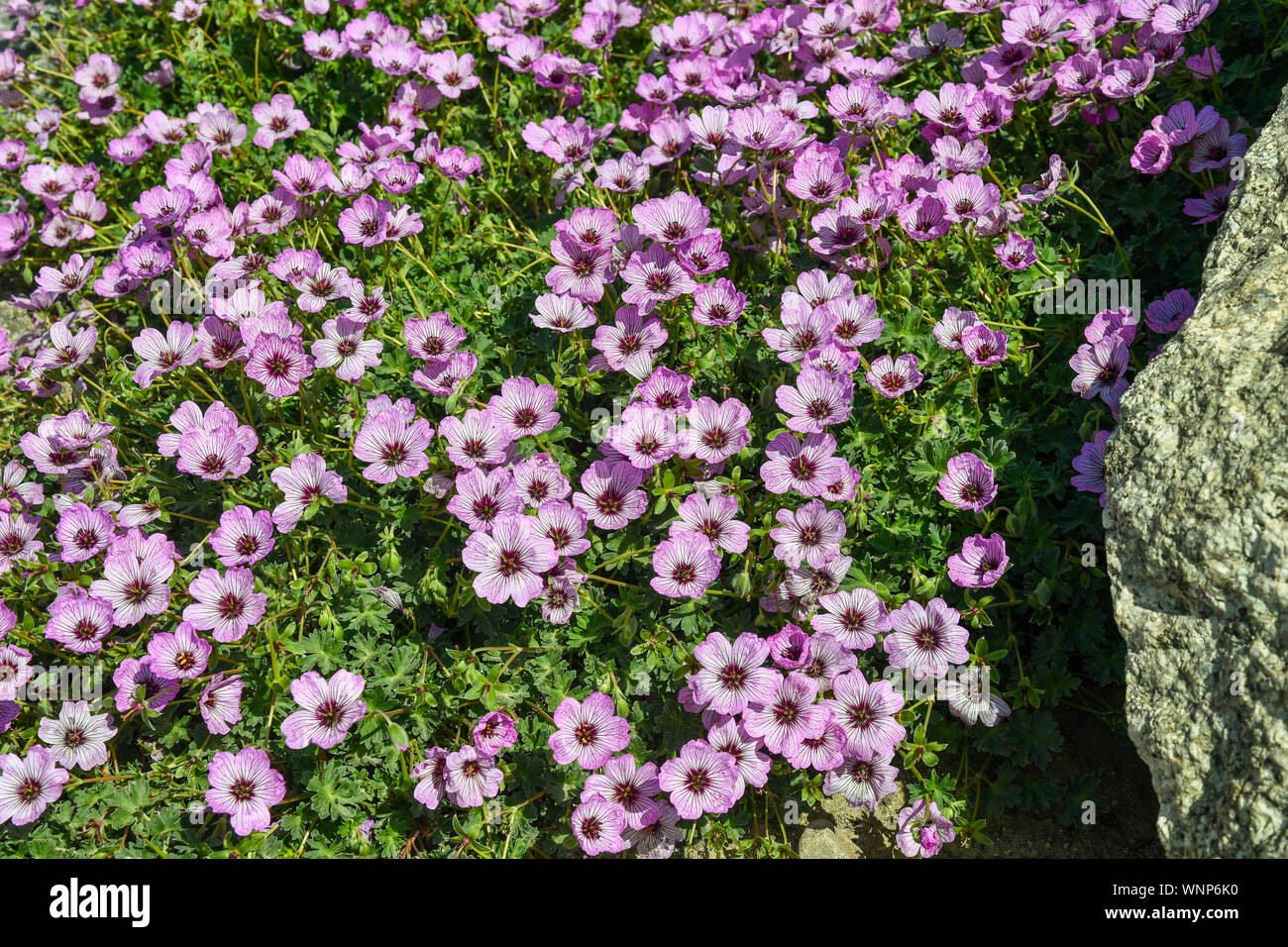

A clump-forming perennial with pinnate, toothed, hairy mid-green basal leaves to 30cm long. Clusters of 3cm wide saucer-shaped magenta-purple flowers have dark spots on the upper petals and are freely borne on long stems from early summer to early autumn

The Royal Horticultural Society is the UK’s leading gardening charity. We aim to enrich everyone’s life through plants, and make the UK a greener and more beautiful place.

The Alpine Stork’s Bill (Erodium cicutarium) is a delicate yet hardy mountain flower found in alpine regions around the world. With its wispy fern-like leaves and showy pink to purple blooms, this plant has captivated botanists and nature lovers alike. But what lies beneath the soil, supporting those dancing floral displays? In this article, we’ll explore the intricate root and stem systems that allow the Alpine Stork’s Bill to thrive in harsh alpine environments.

The Shallow, Widespreading Roots

To survive in thin rocky mountain soils the Alpine Stork’s Bill has developed a shallow, fibrous root system. Rather than growing deep into the ground, these roots spread out horizontally just below the soil surface. This allows the plant to efficiently absorb water and nutrients from the top layers before they drain away.

The roots form an intricate web, with fine secondary and tertiary rootlets branching off the main taproot. This increases the surface area for absorption. Some roots even form symbiotic relationships with mycorrhizal fungi, which help shuttle more nutrients to the plant in exchange for carbohydrates.

This widespread, shallow root network also anchors the plant firmly so it can withstand high alpine winds. But the roots lack woody tissue, so they remain flexible enough to avoid damage when gusts cause the stems to bend.

The Wiry, Wind-Resistant Stems

From the compact rosette, multiple slender stems emerge, reaching anywhere from 5-40 cm tall. These photosynthetic stems are covered in microscopic hairs that provide insulation from intense sunlight and prevent excess moisture loss in the dry mountain air.

The stems display an open, branching growth habit but remain fairly stiff and wiry. This allows them to act as struts, keeping the delicate pink or purple flowers lifted up above the leaves to attract pollinators.

Yet despite their stiffness the Alpine Stork’s Bill’s stems are adapted to survive in windy conditions. They lack thick woody tissue and remain somewhat flexible so they bend instead of break when buffeted by gusts. The stems may take on a flagellated windswept appearance at high altitudes.

Flower Support and Reproduction

The small but showy blooms appear at the stem tips in loose cymes from early spring to fall. The finely-divided fern-like leaves form an attractive backdrop. Inside each 0.5-1 inch flower, the 5 bright pink to purple petals encircle 5 nectar-bearing sepals and a central column of reproductive parts tipped with sticky stigmas.

These complex blooms don’t just look pretty – they serve the critical task of reproduction. Curled sepals hold nectar deep inside the flower, luring pollinators like bees, butterflies, and flies. As these beneficial insects move from flower to flower sipping nectar, they inadvertently transfer pollen between blossoms. This cross-pollination allows the Alpine Stork’s Bill to produce seeds for future generations.

So while underground, the roots and stems work hard to keep the plant alive; above ground, they enable the floral display that drives genetic diversity through pollinator interactions.

Seed Dispersal Adaptations

Once pollinated, the flowers give way to slender seed pods up to 5cm long. These eventually burst open, flinging the seeds out. The seeds themselves have clever adaptations to aid dispersal:

- Hooked barbs and bristles that stick to animal fur for hitchhiking

- An inner awn that moves with humidity, twisting or uncoiling to drill seeds into the ground

- An elaiosome, an oily treat attractive to ants that will carry seeds back to their nests

Thanks to these specializations, seeds scatter far from the parent plant to colonize new areas. This suits the Alpine Stork’s Bill’s hardy, spreading nature perfectly.

From shallow roots that efficiently absorb resources to flexible stems that withstand wind and support flowers, the Alpine Stork’s Bill’s underground and above-ground structures allow it to succeed in the harsh alpine biome. Even the showy blooms and adapted seeds play important roles in reproduction and dispersal. Over centuries, this wildflower has evolved a perfect balance of form and function. By exploring its roots, stems, leaves and flowers more deeply, we can better appreciate the natural wonders that brighten the mountain landscape.

k

REDSTEM FILAREE California wildflowers, Erodium cicutarium; Common Stork’s Bill,Heron’s Bill,Pinweed

FAQ

What are the roots of storksbill?

What are the benefits of storksbill plants?

Is storksbill invasive?

What is a stork’s Bill?

Common stork’s bill or redstem filaree, Erodium circutarium, is flowering now on the plains and in the foothills. Its blooms are small, just 10 to 15 mm across, but such a striking shade of deep lavender that they catch the eye. Each bloom has 5 petals, 5 stamens with anthers, and 5 styles.

What is a redstem stork’s Bill?

Common names: Redstem filaree, redstem stork’s bill, common stork’s-bill or pinweed Family: Geraniaceae Description: Redstem Filaree is a member of the geranium family and is native to Macronesia, Eurasia and Norther Africa. It was introduced to North America in the 18th century, preferring arid areas of the southwestern United States.

What does a stork’s Bill look like?

After the flowers are pollinated, a long, pointed fruit develops, encasing the 5 persistent styles which adhere together to form the stork’s slender, pointed bill, 2.5 to 5 cm long” Stork’s bill is native to Europe, eastern Asia and northern Africa.

Why do stork’s Bill seeds cling to horses?

Stork’s bill seeds have elaborate excrescences (described below) that allow seeds to cling to the coats of horses, cows, deer and buffalo, providing them with the potential for long distance dispersal. But that is just part of the explanation.