The uniquely shaped African spear plant, known scientifically as Sansevieria cylindrica, has long captivated indoor gardeners with its striking cylindrical leaves that point skyward like spears But despite its popularity as a houseplant, the origin of this fascinating succulent has remained shrouded in mystery. In this article, we’ll explore the clues that help shed light on the elusive source of the African spear plant

I’ve always been fascinated by the adventurers and botanists who discovered the exotic plants we grow today. Every houseplant, like the African spear plant, was once found in the wild by an intrepid explorer. These chance discoveries forever changed the horticulture landscape.

Traditional Medicinal Use Offers Early Clues

Indigenous people across Africa have traditionally used the African spear plant for its natural remedies. The Zulus utilized the sap as an insecticide, while other cultures treated ailments like stomach issues, malaria, and skin infections. This widespread medicinal use across the continent provides the first hints that the plant originated somewhere in Africa. But further clues would be needed to pinpoint its exact origins.

The Arab Trade Route Theory

In the 1800s, European explorers took notice of the spear plant’s medicinal powers. Around this time, a theory emerged that Arab traders originally brought the succulent from Africa along ancient trade routes that extended into India and the Middle East.

The arid climate of these trade routes matched the spear plant’s drought-tolerant nature. Its shallow, spreading roots also allowed it to grow without soil while being transported. So Arab merchants could have feasibly carried the spear plant from East Africa, where it grew natively, to new regions along these historic trade networks.

The Madagascar Migration Hypothesis

According to another theory, the spear plant first emerged on mainland Africa but later migrated naturally by sea currents to the island of Madagascar off Africa’s east coast. Humans then potentially spread it from Madagascar to India and beyond.

Evidence shows early African settlers brought many plant species with them when populating Madagascar The spear plant may have been among these transported succulents that found a new home on the isolated island before fanning out across the globe,

Modern Genetic Testing Provides Insights

Advancements in modern genetics have shed further light on the spear plant’s origins. Studies show the greatest genetic diversity by far occurs in wild plant populations centered in southern and eastern Africa. High genetic diversity typically signals a species originated there.

Analyses of modern distribution maps that highlight higher densities of wild spear plants in these same regions reinforce southern or eastern Africa as the most likely place of origin. More genetic testing on wild samples may someday pinpoint the exact location.

An Enduring Houseplant with Mysterious Roots

While its exact beginnings remain shrouded in some mystery, the African spear plant has certainly captured horticultural interest across eras. Its unique adaptations allow it to thrive as a popular houseplant even far from its original African habitat. The allure of this sculptural succulent endures, as we continue unraveling the secrets behind its origins one clue at a time. One thing is sure – the African spear plant has come a long way from its wild roots!

BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH: RAYMOND DART (1893–198 and the “TAUNG CHILD”

Raymond Dart was the first to recognize a fossil hominin in Africa. While his claim to have discovered a human ancestor was not initially accepted by the scientific community, he was vindicated when Robert Broom began finding similar material at other South African sites. The work of Dart and Broom played a pivotal role in directing attention to Africa as the birthplace of humanity, as Charles Darwin had earlier predicted.

Raymond Dart was a renowned Australian anatomist who was teaching at the University of Witwatersrand in South Africa at the time of the discovery. I have read several accounts over the years of the fateful day when the fossil material landed in Dart’s hands. The Taung material was brought to him by either quarry workers or a colleague while he was dressing for the wedding of his daughter or friend, depending on the source you read. He is said to have attempted to use his wife’s knitting needles to extract the fossils from the surrounding matrix. I am not sure why we need to know what he was doing when he got his hands on the goods. We certainly do not know what most paleoanthropologists were doing when they were presented with fossil finds. However, it conjures up amusing possibilities in my mind!

The fossilized remains came from the Taung Quarry in the process of blasting for lime. When presented with the material, Dart established that it was the face, mandible, and endocast (fossilized interior of the cranial vault) of a juvenile hominin. He based this on the anterior position of the foramen magnum and aspects of brain morphology reflected on the interior of the skull vault. Dart named his find Australopithecus africanus, meaning “southern ape of Africa,” and the specimen became known as the “Taung Child.”

The Taung child was two to three years old when it died. We now know that the caves of South Africa were formed by underground water activity and hominins that dropped or were dragged into those subterranean caves became fossilized during the process of speleothem formation. Over millennia, the caves filled with mineral deposits, and via erosion, the mineralized contents and underground cavities surfaced. Many fossils were likely destroyed during quarrying activities, but we are lucky that many were preserved.

Raymond Dart is also renowned for his “Killer Ape” theory and the osteodontokeratic (bone-tooth-antler) culture. Dart believed that animal long bones and carnivore mandibles that were found with australopith remains had been used as weapons to fight and kill one another. We now know that was not the case. They were most likely opportunistically hunting small prey and scavenging larger kills, and they were prey for larger animals.

Raymond Dart is credited with the 1924 discovery and naming of Au. africanus. His now famous “Taung Child” came from the Taung quarry site. The two- to three-year-old juvenile is represented by its face, skull fragments, and mandible, and an endocast of its brain. Dart also worked at the site of Makapansgat. His contemporary, Robert Broom (see biographical sketch below), worked at the caves at Sterkfontein (see Figure 15.4), where he discovered a complete, female cranium known as “Mrs. Ples”, along with other Au. africanus material. Broom also worked at the sites of Kromdraai and Swartkrans; the latter is where he discovered the first paranthropine, Paranthropus robustus. C. K. Brain, a famous taphonomist, also worked at Sterkfontein. He discounted Dart’s views of the australopiths as “killer apes”. He believed that bones either dropped into caves as part of large cats’ prey or were dragged in by rodents for gnawing. Some individuals are thought to have accidentally been trapped in underground caverns. Some speculate that those individuals that show no evidence of having been preyed upon, due to their degree of completeness (e.g. Sts 573 from Sterkfontein and the Au. sediba party from the Malapa site), surely became trapped. The six Au. sediba individuals are thought to have possibly been attracted to the cave by water. Drimolen, a more recently discovered site, has yielded an almost complete cranium as well as material from approximately 80 individuals. A fifth site associated with the species is Gladysvale.

BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH: ROBERT BROOM (1866–195

Robert Broom was a Scottish medical doctor and paleontologist who subsequently made a name for himself as a paleoanthropologist, even though the term did not exist at the time. He taught geology and zoology at a South African college until he was let go for his controversial beliefs in evolution that were contrary to the religious teachings at the college. Subsequent to his termination, his finances went downhill until Raymond Dart’s influence secured him a position at the Transvaal Museum. While his specialty was mammalian-like reptiles, he became increasingly involved with fossil hominins. Together, Dart and Broom made paleoanthropological history, discovering the first and second species of African hominins, respectively. Broom worked at the Au. africanus sites of Sterkfontein and the P. robustus sites of Swartkrans and Kromdraai. All of those sites are now contained within the Cradle of Humankind World Heritage Site. He was the first to discover and name Paranthropus robustus, and his work with Au. africanus helped to support Dart’s claims to have discovered a bipedal ape and human ancestor. Broom’s most famous Au. africanus find was “Mrs. Ples” (possibly a male), which he originally named Plesianthropus transvaalensis or “primitive human” of the Transvaal.

If accounts of Robert Broom are to be believed, he was a colorful character. He is said to have worn semi-formal attire while excavating and when media were present, he conveniently happened upon important discoveries. Supposedly, one of his team buried an artifact that was already labeled with a catalog number. Oh, to have been on the scene and witnessed what must have been an embarrassing situation! Not to mention that, according to numerous online sources, he thought nothing of stripping naked when it became “Africa Hot”! (I picked up that term from a couple of comedy movies but it is now in the Urban Dictionary.)

It is interesting that Broom did not believe in Darwinian evolution but rather, what we would now call Intelligent Design (Wikipedia contributors 2015h).

Au. africanus was more derived than Au. afarensis. This is not surprising considering that they lived at least one million years later, as well as the trend within the hominin lineage to become more encephalized and manually dexterous over time. Au. africanus were habitual bipeds with all of the corresponding lower limb adaptations. They also retained climbing characteristics, such as upward-oriented shoulder joints; long arms relative to legs; and long, curved hand and finger bones. However, in general their hands were more human-like than those of Au. afarensis.

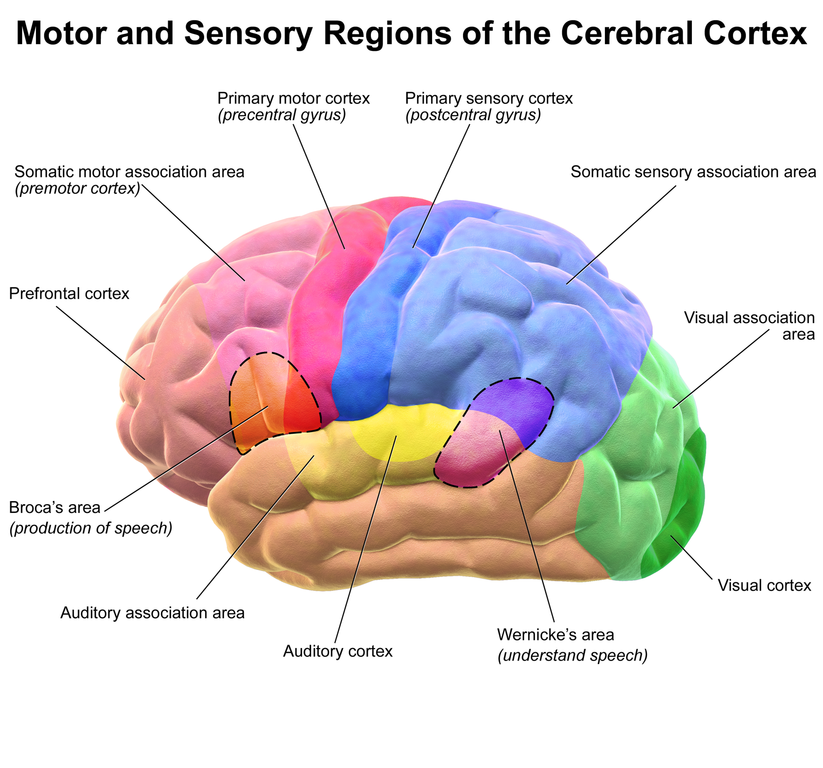

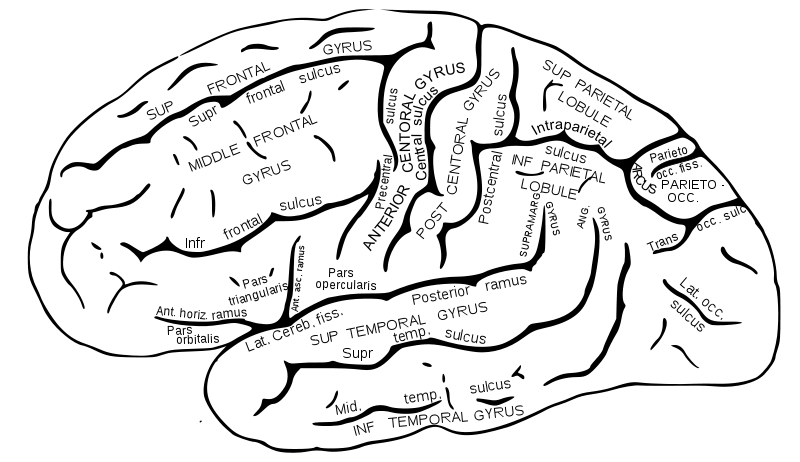

While the brain was small relative to later species, Au. africanus was not only more encephalized than past species, with a cranial capacity of 450 cc (range = 424–508 cc), but also possessed an enlarged cerebral cortex in the frontal and parietal regions (see Figure 15.5). Their encephalization quotient (EQ) was 2.7. The quotient is a method for comparing brain size among species. Anything greater than 1.0 means that the brain is larger than would be expected based on body size (FYI: our EQ is ~7.6). Broca’s area is an area of the left lateral frontal cortex that is involved with the production of language (see Figure15.6). It is present in all Old World monkeys and apes, but it is enlarged in Au. africanus relative to previous species. These are all important developments, in that they herald the appearance of more complex thought processing and likely communication skills. There is debate over whether the lunate sulcus (see Figure 15.7), a fissure on both sides of the occipital lobe that is involved with vision, was more ape- or human-like. The sulcus is smaller in humans than in monkeys and apes.

The external skull reflected the cerebral expansion by becoming more rounded and exhibiting more of a forehead. In addition, the sagittal and pronounced nuchal muscle crests seen in Au. afarensis were not present. However, some males had convergent temporal lines that suggest that they may have had a slight sagittal crest. There is debate over whether the cranial base was flexed (see Figure 15.8), or whether that was a development seen only in more derived forms of Homo.

The species’ face was prognathic with a distinctive concavity in the midfacial region (see Figure 15.9). The dental arcade was more parabolic, and the teeth were smaller than those of Au. afarensis. The first premolar is considered to have been bicuspid, versus semi-sectorial in Au. afarensis. However, their faces were more heavily buttressed for chewing a tougher diet, and some researchers thus consider them to be “robust” australopiths.

They retained the primitive condition of long arms and their finger bones were somewhat curved. However, their hands were more human-like and they possessed our “power” thumb, giving them increased pinching and gripping capabilities. This was accomplished via better developed intrinsic thumb muscles, i.e. within the hand versus coming from the forearm to act on the thumb, and a specialized first metacarpal.

While they were considered to be habitual and very likely obligate bipeds, they still retained a divergent hallux. According to McHenry and Berger (1998) and Green et al. (2007) they may have been more arboreal than Au. afarensis.

Au. africanus were less sexually dimorphic than Au. afarensis, with males averaging 4′6″ (138 cm) tall and 90 lb (41 kg) and females at 3′9″ (115 cm) and 67 lb (29 kg).

Ancient Humans were Scary #ancient #science #evolution #africa #learn

FAQ

What is the history of the snake plant?

How often should I water an African spear plant?

Where did the Sansevieria cylindrica come from?

What does the mother in law tongue plant mean?

Why are African spear plants called spear plants?

The African Spear Plant got its name “spear” due to the tips of their leaves being protected by a tough sharp point. Dracaena Angolensis plant is ranked among the best plants for detoxifying your air.

How do you propagate African spear?

African Spear can also be propagated via leaf cuttings, albeit slowly. Take a stalk and cut it into sections about 3 inches long. After leaving them out to callus, plant them in soil with the right side up. It’s important that they maintain the same orientation as before they were cut. Plants don’t grow upside-down very well.

Are African spear plants native to Angola?

African spear plant, also known as Sansevieria cylindrica or cylindrical snake plant, is a popular houseplant that is native to Angola. It is a low maintenance plant that can thrive in low light conditions and requires minimal watering.

How do African spear plants grow?

African spear plants like to grow in temperatures that are comfortable and mild. Extreme heat and extremely cold climates are not suitable for these plants, and therefore should be grown in greenhouses or in the house in these locations to ensure survival. Temperatures between 50 and 85 °F (10-29 °C) are perfect for these plants.